January 2025

- Luke

- Jan 31, 2025

- 6 min read

Updated: May 3, 2025

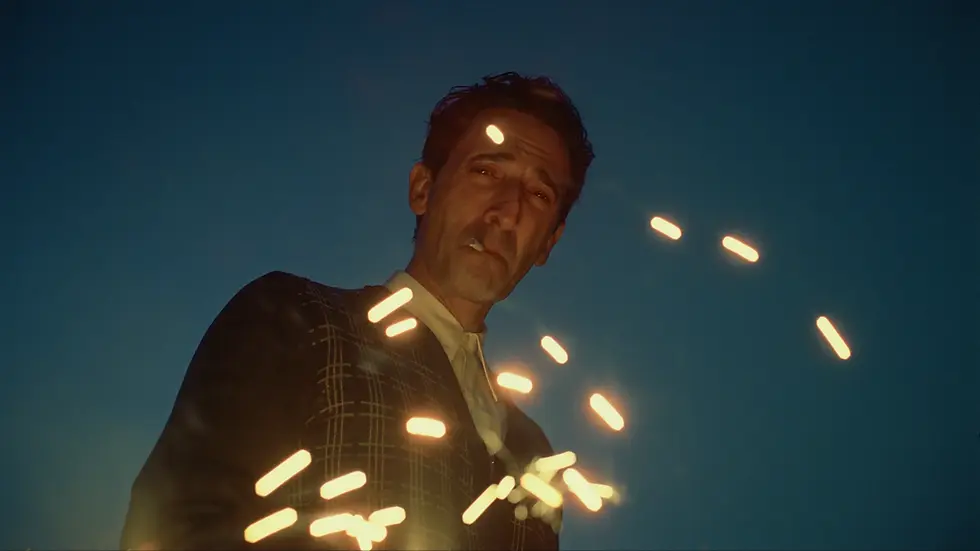

Nosferatu

The term ‘elevated horror’ has always bothered me - it’s the implication that the genre has never been complex or sophisticated, that a stigmatised shlock-fest is now ‘brainy’, and arisen with new life by the auteurist millennial rock-stars of Aster, Peele and of course Robert Eggers: ‘elevated’ is just a trendy, guilt-free pass for insecure moviegoers. But don’t get me wrong, I really do enjoy the work of these filmmakers, but the notion that The Witch is a bougier, smarter alternative to the original Wicker Man or Ken Russel’s The Devils for example, through the shortcut of a contemporary sheen of chic is simply false. If anything, this inflates a director’s persona to a level of blind, fawning adoration. And unfortunately, I feel that’s been the case with Eggers’ rendition of Nosferatu : instead of going for the audience’s jugular, the power lust has gone to his head.

But firstly, there are things in Nosferatu that remind you just how good of a director he is. His use of light, shadow and darkness is no less than inspired, and adds a sinisterly playful sense of obscuring and gradually unveiling the unseen within the frame - this further compliments the finely crafted angular architecture of this spectral world, with shadows looming as tall as the monolithic towers they slink upwards. However, with his visuals on top form, this somewhat leads to the core problem of the film: it seems Eggers has been given free-reign to egregiously indulge in his own style, resulting in an overall narrative that has been vampirically drained of any worthwhile succulence, flow or poetry - in Nosferatu, nothing is sustained. It’s a sporadic, hyperactive display of ill-discipline, echoing that same infantile, excitable fanboyism that Ti West spiralled into with MaXXXine. Elements are presented and then disposed of like a spoiled child on Christmas morning, leaping and flailing between a repetitious formula of a gory, shocking kicker one moment, and then to a solemn conversation the next. For. Two. Hours. I began to reminisce just how tight and stripped-down of an experience The Lighthouse was, the antithesis to Nosferatu’s exhausting conveyor belt of disjointed fluff.

Eggers NEEDS limitations - send him to bed with no supper and ten-million dollars and he just might make another masterpiece, otherwise the yes-men will continue to coddle his meretricious ‘elevated genius'. A certain film from literally 100 years ago understood self-constraint better…

Nickel Boys

The newest edition in the first-person POV pocket of niche, Ramell Ross’ Nickel Boys‘ most astounding achievement is that its unconventional presentation never feels like a gimmick - dehumanization runs rife throughout the Nickel reform school, but Ross counteracts that with the most literal, rawest sense of identification and character embodiment. We feel every swing, whip, glare and hug from the front-row of the protagonists Elwood and Turner’s optics: the theme of the sensory is palpable, but the true greatness of Nickel Boys is that it doesn't just end there. The film's recurrent visual motif of touch, hands clasping and warmly embraces accentuates a desperate cling to living, breathing organisms. The boys, and thus the audience, remember the people and the feeling, rather than concrete artifacts, documents and statistics. Therefore, what Ross has truly crafted is an empyrean transfer of vicarious experience, one in which the purest, most distilled human history lies.

Not unlike Jonathan Glazer’s The Zone of Interest, Nickel Boys explores how atrocities will live on. In the museums, in the tomes, in the web pages, but defying all of that will be primordial streams of human consciousness; something so indecipherable and free-flowing that it could only be captured and preserved through the medium of film. But whilst I would call Nickel Boys thematically genius, as an overall piece it doesn't quite possess the dynamism of its subject, and much like memory itself, oftentimes elongates, rambles and haphazardly drifts off course. It’s a film bursting with voice, and even if it sometimes drags into the monotonous, the core conceit still stands strong: Elwood and Turner let their own individuality, bond and stories define them, not the ones put in place that history will remember. And finally seeing the two friends united, looking back at us in a mirror shot, feels like an ultimate gift.

A Real Pain

Probably one of the most interpretable movie titles of the year, A Real Pain functions as a recursive, 3-stage ladder of grief. In the most benign sense, we have the dynamic between Jesse Eisenberg’s David and Kieran Culkin’s Benji, the latter offering an absolutely electric performance as this crass, yet likable loud-mouth, who you might have guessed, is a tad irksome. “I love him and I hate him” David admits in one pivotal scene, a shifting point in the narrative as Benji’s own turmoil is revealed - his high-strung mask is shed, spotlighting a deep, glazed sadness in their eyes that Culkin evokes wonderfully. But the overarching shadow over the two Jewish cousins is one of a Holocaust tour of Poland: the heaviest, most dire grief of them all, proposing the question if their own personal agonies are menial, self-centred navel-gazing by comparison.

The Russian-doll thematic structure is the film’s most intriguing hook, and paired with the back-and-forth squabbles of the two mismatched kin, it proves to be an enjoyable, if somewhat bare-bones trek. With this only being Eisenberg’s sophomore directorial effort, there is a sense that it feels perhaps too comfortable adopting the formula of a classic neurotic indie, Sundance-y mould: it’s personable and minimalist, maybe to an overly simplistic degree - however, when it does dip into its weightier tone, some of the film’s strongest moments arise. This extends to the first and final shots: a cyclical schlep, that starts and ends with Benji sitting emotionless in an airport, that I personally feel conveys the closing statement on grief as the great leveller: no matter the grandeur or significance, no matter the individual experience, all pain is carried with you - invisible, but all-consuming within.

The Brutalist

As Adrien Brody’s László Toth emerges from the labyrinthine pressure-cooker of a ship’s roaring bowels, the first sight that greets us is an upside-down Statue of Liberty. An image that already feels iconic, the audience is as disoriented as Toth is: a fish-out-of-water flung into a so-called ‘land of opportunity’, there's something sinister about the literal twisting of such iconography, like a bizarro charade or uncanny replica, and a sense of two-faced foreboding. It’s this visual thesis that serves as a synecdoche for The Brutalist - director Brady Corbet unmasks the succubus of the American Dream, in one of the most politically scathing films I’ve seen in a while.

The Brutalist is big. Bigger than big. Corbet’s craft on display is stratospheric, with a magnetic absorption on the viewer and enveloping them into a meticulous, methodical sculpt of an entire life and career, a blaring, leviathan score as its fanfare. Not to mention the intermission, segmenting this 3 hour epic, turning the very act of watching the film into a bona fide, cinematic event: Part One primes the audience with a sense hope, but Part Two slowly dismantles that, when the true, callous exploitation of László is unveiled under the name of American assimilation. However, it’s miraculous that even after that gargantuan runtime, I was still craving another hour or so! You’re bombarded with information; interweaving relationships and conundrums that still haven’t settled in my now throbbing cranium - it’s a dense 3 hours, with performances (especially Brody) that keep the emotion subtle and self-contained, much like the liminal constructions the characters find themselves in. I think that’s The Brutalist ‘s greatest strength and greatest weakness, is that I wanted more of it, just to pierce that probably marble-encrusted surface, impervious on a first viewing.

But László’s harrowing plight has undeniably left me with so much, most notably its last lines. “It’s not the journey, it’s the destination”, to me, was the final note of crushing defeat. Two nations built upon blood-shed, America and Israel, as the terminal reward for the immigrant artist, trapped in their own architectural mazes, fuelled by the manipulation of their very own talents. The conclusion makes us reflect on what both countries stand for today - The Brutalist isn’t about the past, but a painful reminder of the present.